I’ve been eagerly awaiting its impolite entrance, vexed by its simplicity cloaked as an exceptional narrative. And as it awaited its dizzying climax to truly reveal itself as an extraordinary game, Nier: Automata left me with a newfound fondness.

A Challenging Journey

There are moments that defy explanation, and those are the marks of works that linger long in our memories. Yet, long before it enraptured me, N:A took its time to thoroughly exasperate me.

There are games that demand a particular, if not exceptional, level of investment. N:A might not fall squarely into that category, but I was determined to approach it with the utmost dedication. So, I can say I played it properly. Long sessions of about two hours each, uninterrupted, were the norm.

I mention this to the reader because it’s crucial. My 39-year-old brain, burdened by the responsibilities of a young parent at the time, required much more time and tranquility than it did just five years prior. This is especially true when dealing with a J-RPG, a genre known for its demanding nature.

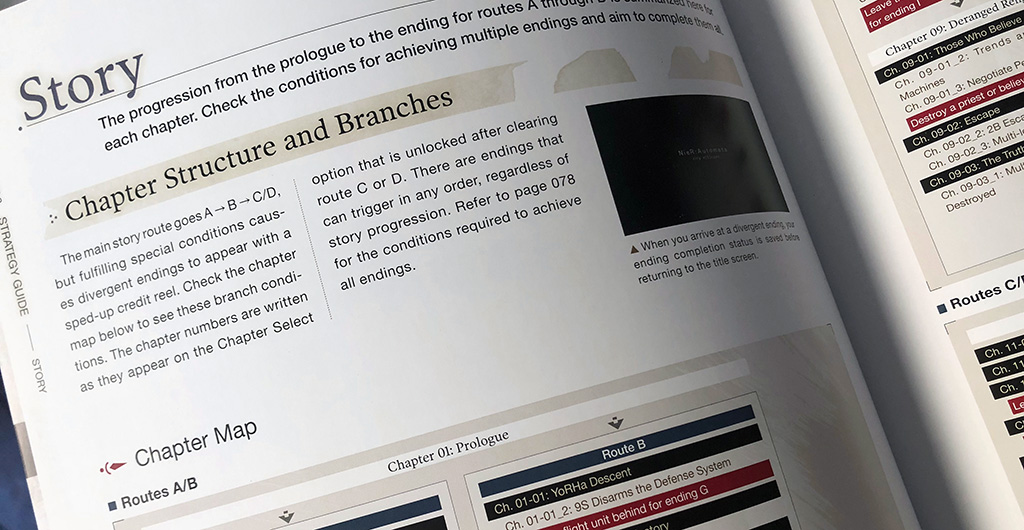

As part of the experience, I obtained the “World Guide – vol. 2,” which, in addition to being a strategic guide, proved to be precisely what it claimed to be—a genuine guide to the world crafted by the mind of Yoko Taro, its creator. Manga volumes were also at my side, courtesy of a French publisher releasing them just as my gaming sessions began.

The anime adaptation had started airing a few days earlier, and I managed to watch the first episode the day before I completed the final act. All of this seemed quite late for a title that had been around for five years (or more?). Why now, just as I delved into it? Was it a sign, one of those universe-nudges? A heavy-handed nudge that N:A doesn’t shy away from?

In any case, this transmedia endeavor at which N:A excels had the unintended consequence of making it challenging for me to detach from its world. Once the task was complete, I felt a genuine struggle to move on, even though I had no intention of starting the game anew. We’ll return to that.

However, I watched it as a “game movie” immediately after completing my run. It had become almost obligatory for every game whose story I cherished, a second layer of paint confirming the first and filling the gaps. This viewing served to solidify my overall understanding of the story, shielded from the temptation of grinding, a temptation I rarely resist, especially when it’s well-executed. It was, in fact, quite an enjoyable game movie to watch, with smooth progress and a well-paced narrative, even devoid of its gameplay loop. N:A has this going for it as well, in addition to its intrinsic qualities: it’s enjoyable to watch.

Meta-Narrativity and Eye-Rolling

Oh, how many times did my eyes roll to the heavens at the acrobatics of its narrative, executed with the confidence of a champion, when I hadn’t asked for anything truly exceptional? When my credulity was stretched far beyond its limits? I quickly grew weary of the reflex to justify every game mechanic with narrative, always more narrative, meaning, and justification, simply annoying.

Yes, here, everything is covered. The narrative web is an all-encompassing insurance policy, triggered when you die or use fast-travel, justified by some convoluted tale of transferring to a temporary body, undermining logic more than if they had relied on the suspension of disbelief. Fast-travel that conveniently breaks down whenever it pleases, like a Parisian subway elevator. And in both cases, the dramatic effect produced is consistently lackluster and inevitably leads to sighs.

The execution of scenes doesn’t fare much better. We can appreciate the unconventional choices made to create contrast and, as a result, style, but sometimes, it simply doesn’t work. Yes, it’s nothing short of a failure when one of the most crucial dialogues, the one with Adam and Eve, takes place in the midst of a noisy battle, blaring music, barely audible text, and subtitles obstructed by demanding gameplay… a nod to accessibility advocates would have been appropriate.

Insolence, Yet Again

And how can we not mention the most grandiose dramatic bluff ever executed in a video game, or perhaps even in any work of art? The most conceited and ill-mannered, the most arrogant and outdated farce ever attempted? What other game has the audacity to believe that its first act is so exceptional that it must be played twice in a row?

Yes, I understand the meta-commentary, the application of “same player plays again,” drawing from the grammar of video games, an art enshrined by prestigious academies. But it’s a tribute I refuse. I refuse it because, once again, it annoys me, looks down on me. Yes, I noticed that the enemy’s projectiles resonate with a whole shmup culture. Yes, I know that shmup is the purest, noblest discipline in the world of video games. I know all that; I’ve heard the 8-bit music playing with it, always carrying the subtext of “only the true fans know.” I’ve seen it all, and no, it won’t make me accept that I had to replay the first act without any additional content other than the expert’s borrowed commentary.

What effect is this supposed to have, aside from confusion? To sow doubt that it’s not a bug? I confess, I consulted the guide to determine if I had taken a wrong narrative branch somewhere. But yes, this loser’s branch, the one that makes you question the wasted time, the branch that leads you to spinsterhood in otome games? No, it wasn’t a bug. N:A makes you play the first act twice. That’s just how it is. And don’t expect any narrative subtleties between the two realities created. We’re not in “LOST” or “Groundhog Day.” We’re replaying. The same. That’s it. No need for a spoiler section. It’s exactly the same content, the same dialogues, the same battles. Nothing changes. Now, get to work.

In the end, it’s not just arrogance; it’s downright impoliteness.

But when it doesn’t completely infuriate, this arrogance can make you smile—a genuine, honest, and blissful smile. Like that hidden cave in the desert where endless waves of enemies arrive, and the game remains acutely aware that its flawless combat, stamped with the legendary seal of “Platinum Games,” is enjoyable without interruption, offering unhindered pleasure. This time, it’s forgiven.

So, it’s in these secret caves, these off-the-beaten-path moments, that N:A finds its path to redemption. Once the ill-conceived joke of playing the first act twice is over, and once you have a better grasp of the world after being reintroduced, you must acknowledge that some contrasts in the scenography hit the mark.

I particularly think of the chilling scene where the most significant secret of the story is revealed. A distant camera, no music. The Commander gives up… then a simple, brief text. The deception is delivered almost accidentally, emphasizing the obsolescence of humanity’s fate even more. In my view, this scene of the grand

revelation is one of the most successful in the game, presented as a mere formality, something to accept without ceremony. There’s still a game to finish, a game that refines and asserts itself with each chapter, but its dramatic fate is sealed.

Contrasts and Contortions

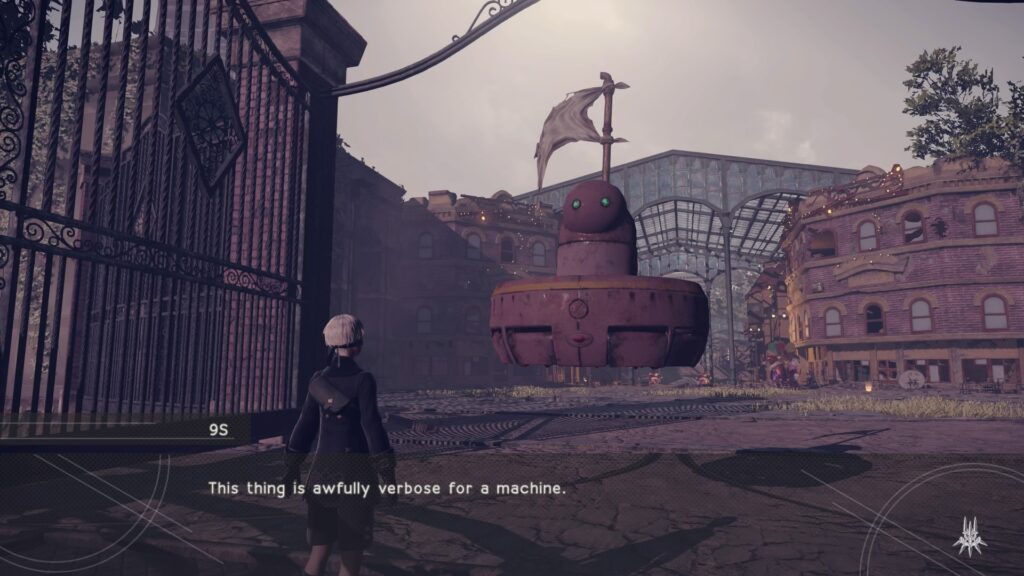

N:A is keen on using the image of robots attempting to humanize themselves, with scenes featuring androids in tin cans pathetically imitating human behavior. However, it’s not necessarily in these numerous, heavy-handed scenes, accentuated by cliché musical cues, that the most beautiful contrast can be appreciated.

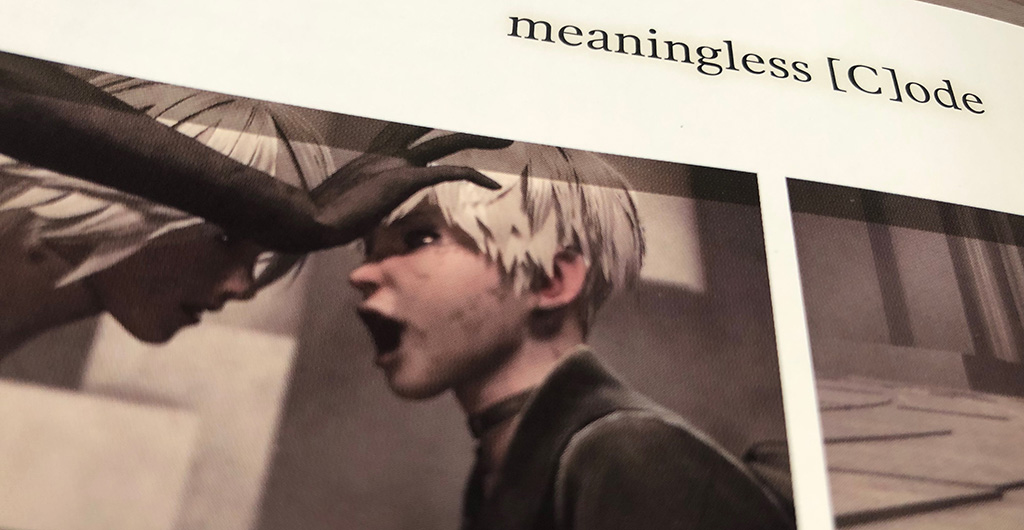

Intermittently, the verbosity, imagery, and references to all things technological are punctuated by crude impalements, painful strangulations, and bloodstains. A small effort in imagination and a reward for our curiosity to perceive, here and there, a true display of contorted faces. Through pain or agony, slight deformities disturb the gaze and impression. Eve and his final attack, with a charred and distorted face, unsettles and stands out. 9S, full of rage as he swears to massacre all 2B models, with a jaw that seems ready to detach from his skull, is unsettling. The last “fake” 2B on the ground, summarily executed by 9S, is also unsettling. So many twisted, shattered, and swollen faces convey much more meaning and attachment than anywhere else in the game. It all revolves around pain.

9S has this sole function of remaining far too idealistic and slightly normative not to completely derail in the final act. He does everything too perfectly from start to finish, and the unraveling, the twisting, the crumpling gradually become inevitable. By suppressing his desires, particularly the desire to “be with” 2B, which hides deep within the drawers of unspoken words and shame, there, concealed in the machinery, 9S rushes, smiling, toward a pit of disappointment and rage in the final act, where he won’t be given any chance to prove his worth. On the contrary, all his rectitude only hastens his downfall when the machines subject him to a terrible psychological torture session in the last tower.

Always Something to Play, Nevertheless

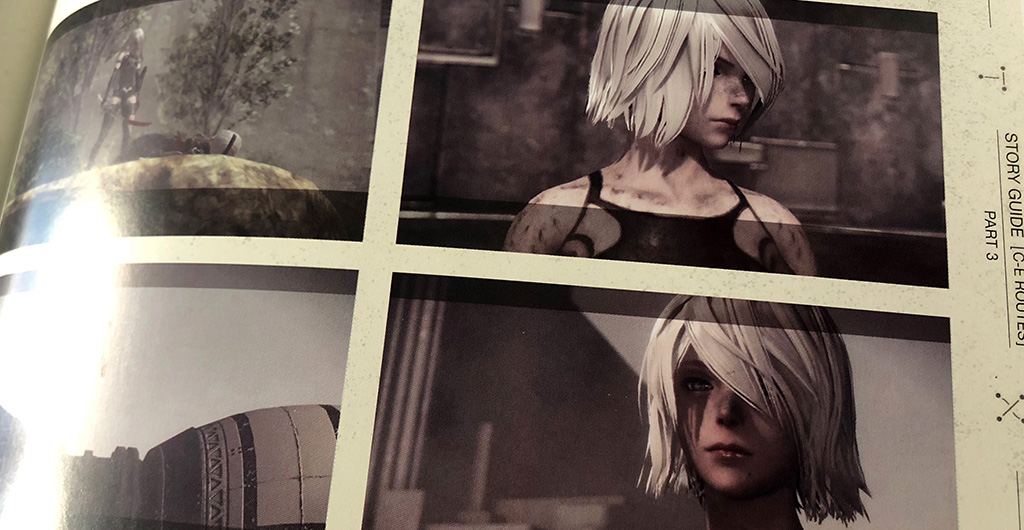

For me, the shift occurred with the arrival of 2E. The game had finally put an end to its unbearable casuistry and had just completed a marathon of flawless gameplay. A cathartic sacrifice had been executed, and any hope of salvation for humanity had evaporated long before the start of the final act. The game leaves us sneakily, like a robot tasked with completing its program to the very end.

The assimilation of 2E into 2B is just strange enough to work. Her aggressive attitude toward the overly talkative bots, present from start to finish, is most welcome. A2 is like a promise of an afterlife, an anti-spectacular and disillusioned outcome, where the past fades into relativity and doubt. She also served as a mirror of my state of mind regarding the game, which had taken me from annoyance to emotional exhaustion. And, like 2E’s response to her chatty pod, I threw a much-needed “urusaï damare” at the game through her. In other words, a good old “shut your mouth.”

The entire build-up to the final showdown, when 9S hacks the last tower and the twins come to his aid, is for naught. It’s a very strange sensation to participate in this surge of power that, anyway, we know will lead to so little, as what there is to save is symbolic. Once we know humanity is a lost cause, we’re left with significantly hopeless stakes, like a bitterness that taints the freshness.

Everything feels like one battle too many, which gives the final showdown against Eve a unique flavor. And finally, after endless conflicts with aggressive bytes, nothing left me more appreciative and content than the final words uttered by 2E, facing a radiant sun. The last word was the right one; beauty, at last, seems able to redeem everything else.

The Best Music Piece

Everything has been said and celebrated about the extraordinary soundtrack of N:A. So, I will celebrate just one piece here. A gem that encapsulates the boundless melancholy of this rather peculiar tale in just one melody, one that you can listen to over and over again.